For someone whose research and teaching life has

been spent mostly outside of traditional schooling contexts, I spend a great

deal of time thinking about school. And most of the time I worry that what's

happening in schools is not education(al); or perhaps, what schools educate

about isn't necessarily the content of curricula but rather the disciplined and

disciplinary discourses of school(ing). We learn that we must sit quietly to

learn effectively, to do our own work without the help of others, and that

reading in silence without moving our lips is the superior hallmark of decoding

fluency; in fact, making noise of any kind is akin to depending on squeaky,

bothersome, always-temporary training wheels that signals one's lack of

proficiency in being a student. And this is even before we get to any mandated

testing.

I learned all of these things and more during my years in school, a journey which began when I was just two and half years of age. Some part of me must've liked the institution enough to continue on through the completion of a PhD -- in total, 26.5 years of school. We had a good relationship, School and I, but I doubt that I would say the same if I were to have gone through schooling in today's era of test-first-think-later.

Earlier this month, I had the great privilege of spending some time with colleagues at the University of Tasmania, the Launceston campus, where the School of Education hosted a two-day conference on New Literacies, Digital Media, and Classroom Teaching (#UTASNewLits). The conference, organized by Angela Thomas (@anyaixchel), reflected an ethos I have come to love in Angela's research and writing (in brief: focusing on identities and practices in an age of new and digital literacies, but oh, so much more): a persistent sense of being present in the current communicative moment while considering what possible directions new modes, modalities, and digital platforms present for how we imagine, enact, and design education. (Notice, I did not say schooling.) My reflections on the time spent down under has continued to remind me that when educators are brought together, even as testing and schooling may loom large, they are really passionate about education -- the possibilities of creative, imaginative, innovative engagement with the world.

I learned all of these things and more during my years in school, a journey which began when I was just two and half years of age. Some part of me must've liked the institution enough to continue on through the completion of a PhD -- in total, 26.5 years of school. We had a good relationship, School and I, but I doubt that I would say the same if I were to have gone through schooling in today's era of test-first-think-later.

Earlier this month, I had the great privilege of spending some time with colleagues at the University of Tasmania, the Launceston campus, where the School of Education hosted a two-day conference on New Literacies, Digital Media, and Classroom Teaching (#UTASNewLits). The conference, organized by Angela Thomas (@anyaixchel), reflected an ethos I have come to love in Angela's research and writing (in brief: focusing on identities and practices in an age of new and digital literacies, but oh, so much more): a persistent sense of being present in the current communicative moment while considering what possible directions new modes, modalities, and digital platforms present for how we imagine, enact, and design education. (Notice, I did not say schooling.) My reflections on the time spent down under has continued to remind me that when educators are brought together, even as testing and schooling may loom large, they are really passionate about education -- the possibilities of creative, imaginative, innovative engagement with the world.

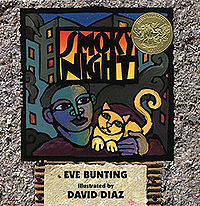

It was perhaps telling that the opening keynote was delivered by the esteemed Len

Unsworth, whose respectful discussion of children's books and the new media

forms into which they become translated was at once incredibly engaging and

illuminating. How does the point of view of the narrative change when a printed

book is made into a film, he asked as he proceeded to delight the audience of teachers,

researchers, and students with a read aloud of “The Lost Thing” by Shaun Tan. Len

invited us to shift our gaze to various parts of the text, that he had scanned

and enlarged as slides from which he read. What was the reader able to

determine and what information on the page allowed such interpretations? From whose

vantage point was the reader being brought into the narrative, and how did the

point of view inform our understandings of what was going on? What was said and

left unsaid? Then he showed us clips from an animated version of the story,

pointing out the affordances of this medium to fill in gaps left by the printed

text. Swift camera moves shift perspective in the blink of an eye – first, we

see what the boy sees and in another instant we are looking down on the boy as

if we are one with The Thing. What impact might this have in the story we make

in our heads of the story we are reading or watching. I think of an essay

written by Amelie Rorty, described as a philologist in her short bio, in which she

talks about some of the many possible questions one might ask of an author when

engaging with one’s text. She describes this as a practice of understanding the

“author’s house,” and in one sense I understood the careful and thoughtful

analytic framework that Len and colleagues, Annemaree O’Brien and Paul

Chandler, have developed as another approach to understanding the author’s

house, particularly through a focus on the representation of point of view.

Lucky for the rest of us, their co-authored book will be available in early

2012!

Point of view was turned on its side in the morning

workshop I attended in which Winyu Chinthammit led us through the process of

using software to generate 3D holograms in pursuit of a hands-on understanding

of augmented reality, a research and development agenda that is alive and

kicking at the HITLAB at UTas. As I manipulated a magenta cube on the marked

paper in front of me, I wondered about how access to this sort of object play

might inform narrative creation. How else might we use the affordances of augmented

reality software for a range of educational purposes, not only inside but also outside of school?

One

of the really lovely things about intimate conferences in which choice times,

like a selection of workshops, are punctuated with talks that all participants

attend is that a shared lexicon develops quickly. The afternoon keynote by

Martin Waller, the charming and enthusiastic primary teacher and researcher

from England deepened shared lexicon by cultivating our appreciation for the

affordances of social media as he regaled with tales of his tweeting adventures

with Year 2 students (approximately seven year olds). Martin spoke of what he

called “contentious literacy” or those practices of literacy embedded social

media that do always have a ready place in schools. His goal, however, is

broader than test preparation and the adherence of some pre-fabricated

curriculum. Martin wants his students to explore, and to feel a sense of pride

and connection and joy from and through their literacy engagements. And

these are among the results to come from setting up a (fully protected!)

twitter account through which the world can learn of the Year 2 kids’ excellent

adventures as they write poetry, go on treasure hunts, plant a garden, and

learn more about themselves and the world in which they live. Martin shared one

response from a fellow literacy blogger and tweeter, @librarybeth, whose

appreciation for the daily musings of his students delighted them equally and

served as additional motivation for continued social media composing. He

pointed out, too, the ways in which social media such as twitter can

organically nurture the critical literacies of young children, pushing them to

wonder aloud and not remain complacent in their inquiries.

Day 1 concluded with another set of workshops and I

was excited to facilitate a workshop on multimodal response and share the worlds of Media that Matters Film Festival (and the

film Immersion) and the online video making tool Animoto with an amazing group.

Stay tuned for part 2 --